Researchers have investigated the link between environmental factors and gastrointestinal symptoms for decades. In 2004, a group of scientists at Monash University was the first to use the term “FODMAPs” to describe a specific group of carbohydrates that includes Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, And Polyols. These researchers proposed the “FODMAP hypothesis”, which associated FODMAP intake with the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. (9) Since then, a low-FODMAP diet has been considered a first line of therapy in functional gastrointestinal disorders and has been shown to improve gastrointestinal symptoms by approximately 70% in certain individuals. (15)

Read on to learn about the low-FODMAP diet, as well as which health conditions may benefit from the diet.

What is the low-FODMAP diet?

The low-FODMAP diet, sometimes referred to as the FODMAP diet, is a dietary intervention that restricts foods containing highly fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols. These short-chain carbohydrates and polyols are poorly absorbed in the digestive tract and reach the colon where they are fermented by bacteria, a process that may result in certain gastrointestinal symptoms including gas, bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. (1)(3)

Low-FODMAP diet plan

The low-FODMAP diet plan generally consists of three phases:

- Restriction, where all FODMAPs are restricted from the diet for a period of four to six weeks.

- Re-challenge, where high-FODMAP foods are reintroduced by FODMAP sub-group to identify personal triggers and tolerance levels.

- Personalization, where individuals follow an individualized long-term low-FODMAP diet based on their personal tolerance. (2)(11)(14)

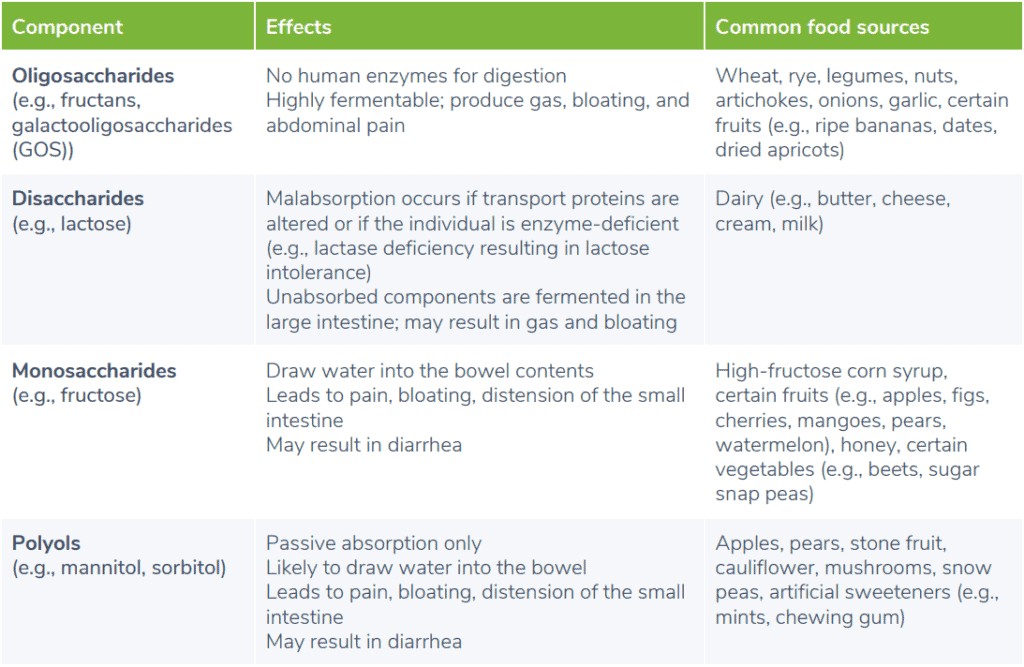

Low-FODMAP diet chart

The low-FODMAP diet chart below outlines dietary FODMAPs, their gastrointestinal effects, and common food sources in which they are found. (3)(8)(12)(14) These food sources are generally restricted on a low-FODMAP diet plan.

How does the low-FODMAP diet work?

The low-FODMAP diet works by restricting the intake of dietary components that may be contributing to an individual’s gastrointestinal symptoms. FODMAPs are osmotically active, which means they have the ability to draw water into the space inside the intestines, known as the lumen. This increased water volume may result in intestinal distension and associated symptoms, such as abdominal pain. Dietary FODMAPs may also negatively affect the gut barrier, immune response, and gut microbiota, resulting in GI symptoms. (1) Limiting dietary intake of FODMAPs may lower intestinal water content, and reduce fermentation and gas production in the colon. Research has shown that the low-FODMAP diet may also reduce levels of pro-inflammatory compounds, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-8 (IL-8). As with any other dietary protocol, the outcomes of the low-FODMAP diet plan will vary depending on the individual, and may be affected by various factors, including microbiota composition. (1)

Clinical significance: who should follow a low-FODMAP diet?

While FODMAPs are always poorly digested, healthy individuals may not experience any adverse gastrointestinal symptoms. (11) Research has shown that the low-FODMAP diet may benefit individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease (CD), and non-coeliac gluten sensitivity, as well as healthy athletes who experience gastrointestinal issues during training.Low-FODMAP diet for IBS

The low-FODMAP diet can benefit individuals suffering from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a group of functional gastrointestinal disorders that affects approximately seven to 15 percent of the general population. (1) Results of a meta-analysis showed that patients on a low-FODMAP diet experienced a greater reduction in symptoms of pain and bloating compared those following a high-FODMAP diet or a traditional IBS treatment diet. The traditional IBS diet is widely recommended and involves restricting trigger foods, such as dairy products, fructose, wheat, beans, onions, and cabbage, as well as limiting the intake of alcohol, caffeine, high-fat foods, and fiber. (1) The low-FODMAP diet may be particularly beneficial for patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D). In a randomized, controlled trial of 110 patients with IBS-D, individuals were assigned to either a low-FODMAP diet plan or general diet advice group for six weeks. While both groups experienced improvements in symptoms, including distension, stool consistency, and stool frequency, the improvement was greater in the low-FODMAP group. (16)Low-FODMAP diet for inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Research examining the effects of FODMAPs in individuals with these conditions has found that dietary FODMAP intake exacerbates functional gastrointestinal symptoms. (5) A pilot study of the Low-FODMAP diet in patients with CD and UC was shown to reduce abdominal symptoms, such as pain, bloating, diarrhea, and wind. (7)Low-FODMAP diet for celiac disease

Celiac disease (CD), a chronic condition affecting genetically-susceptible individuals, is characterized by an autoimmune reaction triggered by the ingestion of gluten, a protein found in certain grains (e.g., wheat, rye, and barley). Individuals with CD commonly experience comorbidities, such as functional gastrointestinal symptoms and symptoms of IBS. A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study was conducted in CD patients with co-occurring IBS and functional GI disorders who had adhered to a gluten-free diet for at least one year. Participants were placed in either a gluten-free low-FODMAP diet treatment group, or regular gluten-free diet control group. After 21 days, a reduced global score on the symptom checklist was found in the treatment group but not the control group. A higher improvement in general well-being was also seen in the low-FODMAP diet group. (1)Low-FODMAP diet for non-celiac gluten sensitivity

Dietary FODMAPs may also be a contributing factor to intolerance of gluten-containing grains in patients with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. A randomized, placebo-controlled study examined the effects of a low-FODMAP diet in individuals with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity. The researchers evaluated diet and symptoms prior to the intervention, and found that some participants experienced symptoms despite adhering to a gluten-free diet. The participants were then instructed to follow a gluten-free, low-FODMAP diet for two weeks. Compared with the baseline gluten-free diet, following a gluten-free, low-FODMAP diet improved symptoms, such as bloating, abdominal pain, wind, and fatigue. (4) Participants were then divided into three diet treatment groups, either high-gluten, low-gluten, or placebo, for one week. In the group that introduced gluten, only 16% of participants experienced an increase in abdominal symptoms. The authors suggested that reducing the fructans present in gluten-containing grains may be responsible for the improvement in symptoms following a gluten-free diet, rather than the removal of gluten itself. (3)

Low-FODMAP diet for athletes with gastrointestinal symptoms

Recreational and competitive athletes may experience increased gastrointestinal symptoms, such as loose stools or diarrhea, following exercise. Strenuous activity impairs gastrointestinal integrity and function, resulting in undigested food molecules which have an osmotic effect in the small intestine. Athletes consuming high amounts of carbohydrates necessary for fueling exercise may experience exacerbation of FODMAP-related gastrointestinal symptoms. (12) Preliminary research in runners following a six-day low-FODMAP diet intervention suggests that a short-term low-FODMAP diet may minimize exercise-related GI symptoms. (11) Furthermore, athletes may already be making the connection between dietary triggers and their digestive symptoms. A survey of 910 athletes found that over half of the athletes eliminate at least one FODMAP food, with over 80% experiencing improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms as a result. The most commonly restricted FODMAP was lactose, a sugar found in milk and dairy products. (11)Further considerations

While research has yet to examine the long-term implications of the low-FODMAP diet, research on other elimination diets suggests that long-term elimination may result in lower intake of certain nutrients. For example, restriction of dairy may lead to low levels of calcium in the diet. (5) When eliminating any individual food or food groups, a well-planned diet helps to ensure nutrient needs are met through other dietary sources. There are also concerns about a low-FODMAP diet negatively impacting the gut microbiota. Studies have shown that a low-FODMAP diet may reduce total bacterial abundance, as well as counts of Bifidobacteria and beneficial short-chain fatty acids. (5) However, the adverse effects of the diet on microbiota may be mediated by administering a probiotic supplement. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of 104 patients with IBS found that combining a multi-strain probiotic supplement with the low-FODMAP diet increased the quantity of Bifidobacterium species compared to a low-FODMAP diet with placebo. (13) A small 2021 randomized controlled trial explored whether a web-based low-FODMAP diet intervention and probiotic treatment were equally effective in reducing symptoms of IBS. After 4 weeks, 57% of patients in the low-FODMAP diet group experienced a minimum 50-point reduction in the IBS Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS). Additionally, 38% successfully reintroduced a median of 14.5 high-FODMAP foods. In the VLS#3 probiotic group, 62% of patients experienced a minimum 50-point reduction in the IBS-SSS. (2) No significant difference in symptom reduction was observed between the low-FODMAP diet and probiotic treatment groups, suggesting that both approaches are equally effective in managing IBS symptoms. (2)The bottom line

The low-FODMAP diet involves restricting certain dietary components, known as FODMAPs, which have been associated with various gastrointestinal disorders and symptoms. (14) Researchers recommend that a low-FODMAP diet should be individualized to minimize the level of restrictions and any associated psychosocial or nutritional risks. (11) Be sure to speak to your integrative healthcare practitioner for guidance when implementing dietary and lifestyle changes.- Altobelli, E., Del Negro, V., Angeletti, P. M., & Latella, G. (2017). Low-FODMAP diet improves irritable bowel syndrome symptoms: A meta-analysis. Nutrients, 9(9), 940.

- Ankersen, D. V., Weimers, P., Bennedsen, M., Haaber, A. B., Fjordside, E. L., Beber, M. E., Lieven, C., Saboori, S., Vad, N., Rannem, T., Marker, D., Paridaens, K., Frahm, S., Jensen, L., Rosager Hansen, M., Burisch, J., & Munkholm, P. (2021). Long-Term Effects of a Web-Based Low-FODMAP Diet Versus Probiotic Treatment for Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Including Shotgun Analyses of Microbiota: Randomized, Double-Crossover Clinical Trial. Journal of medical Internet research, 23(12), e30291.

- Barrett, J. S. (2017). How to institute the low-FODMAP diet. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 32, 8–10.

- Biesiekierski, J. R., Peters, S. L., Newnham, E. D., Rosella, O., Muir, J. G., & Gibson, P. R. (2013). No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology, 145(2).

- Catassi, G., Lionetti, E., Gatti, S., & Catassi, C. (2017). The low FODMAP diet: Many question marks for a catchy acronym. Nutrients, 9(3), 292.

- Cox, S. R., Prince, A. C., Myers, C. E., Irving, P. M., Lindsay, J. O., Lomer, M. C., & Whelan, K. (2017). Fermentable carbohydrates exacerbate functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over, re-challenge trial. Journal of Crohns and Colitis, 11(12), 1420–1429.

- Gearry, R. B., Irving, P. M., Barrett, J. S., Nathan, D. M., Shepherd, S. J., & Gibson, P. R. (2009). Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease—a pilot study. Journal of Crohns and Colitis, 3(1), 8–14.

- Gibson, P. R., & Shepherd, S. J. (2005). Personal view: Food for thought – Western lifestyle and susceptibility to Crohns disease. The FODMAP hypothesis. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 21(12), 1399–1409.

- Gibson, P. R. (2017). History of the low FODMAP diet. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 32, 5–7.

- Lis, D., Ahuja, K. D., Stellingwerff, T., Kitic, C. M., & Fell, J. (2016). Food avoidance in athletes: FODMAP foods on the list. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(9), 1002–1004.

- Lis, D. M., Stellingwerff, T., Kitic, C. M., Fell, J. W., & Ahuja, K. D. K. (2018). Low FODMAP: A preliminary strategy to reduce gastrointestinal distress in athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 50(1), 116–123.

- Lis, D. M., Kings, D., & Larson-Meyer, D. E. (2019). Dietary practices adopted by track-and-field athletes: Gluten-free, low FODMAP, vegetarian, and fasting. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 29(2), 236–245.

- Staudacher, H. M., Lomer, M. C., Farquharson, F. M., Louis, P., Fava, F., Franciosi, E., … Whelan, K. (2017). A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and a probiotic restores Bifidobacterium species: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology, 153(4), 936–947.

- Thomas, J. R., Nanda, R., Shu, L. H. (2012). A FODMAP diet update: Craze or credible? Practical Gastroenterology, 36(12), 37-46.

- Tuck, C., & Barrett, J. (2017). Re-challenging FODMAPs: The low FODMAP diet phase two. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 32, 11–15.

- Zahedi, M. J., Behrouz, V., & Azimi, M. (2018). Low fermentable oligo-di-mono-saccharides and polyols diet versus general dietary advice in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 33(6), 1192–1199.