A plant-based diet, high in fiber, fermented foods, and prebiotics, can help support your digestive health. (7)

How to improve digestive health naturally

Follow these 9 tips to help address digestive problems and improve your overall digestive health.1. Consume gut-friendly foods and beverages

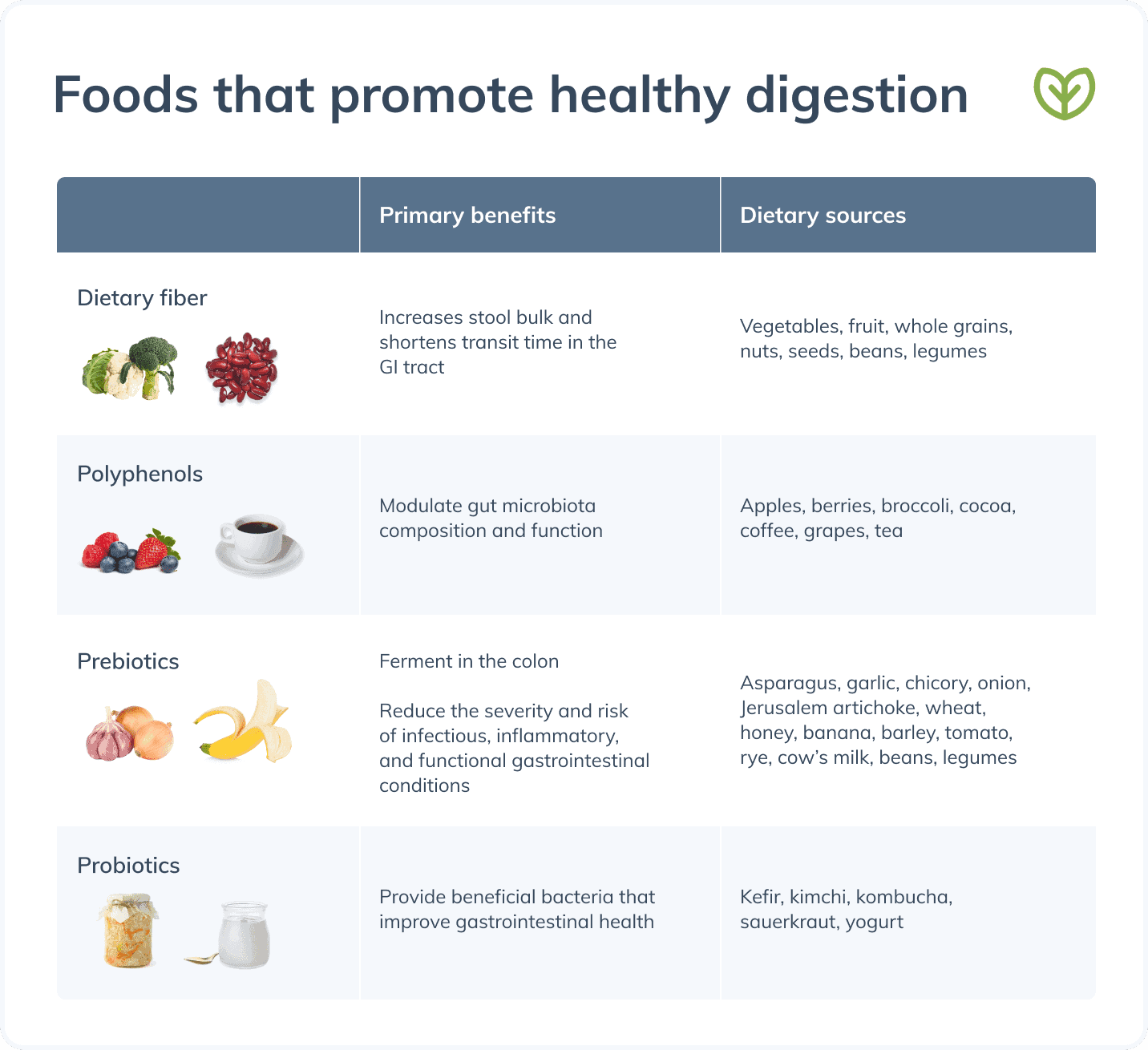

An overall dietary pattern that focuses on increasing plant-based foods and moderating red meat intake may help improve microbial diversity and regulate bowel habits in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), (6) as well as reduce colon cancer risk. (3) The best dietary components and best foods for digestion include:- Dietary fiber, found in whole grains and vegetables, which increases stool bulk and shortens transit time in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (7)

- Polyphenols, plant compounds found in berries, cocoa, grapes, and tea, which can reach the colon and be metabolized by microbiota (7)(11)(20)

- Prebiotics, substances found in a variety of fruit, vegetables, and grains, which are fermented by microbiota in the colon and reduce the severity and risk of infectious, inflammatory, and functional gastrointestinal conditions (7)(8)

- Probiotics, found in foods such as cultured yogurt and fermented foods, which provide beneficial bacteria that improve gastrointestinal health (16)

Did you know? The gut microbiota, which consists of various microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi, helps protect the body against enteropathogens and promotes normal immune function. (14)

Consuming foods rich in fiber, polyphenols, prebiotics, and probiotics can improve digestion.

2. Minimize foods that may harm digestion

Some individuals may benefit from avoiding or minimizing certain foods, as they may damage the gastrointestinal barrier (lining), (3) impair microbial balance, (6) and contribute to or trigger digestive symptoms. (13) Examples include:- Carbonated beverages, which may exacerbate symptoms of dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (9)

- Fructose, a sugar found in fruit and used as a sweetener, which may harm the gastrointestinal barrier and increase the risk of fatty liver disease when consumed in large amounts (3)

- Gluten, a protein found in grains such as wheat, barley, and rye, which should be avoided by certain individuals such as those with celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity (5)

- High-fat diets and large meals high in fat, which may trigger functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (9)(13)

- Saturated fats, typically found in animal protein (meat), dairy products, and coconut, which may increase pro-inflammatory gut microbiota (7)

Overall, a typical Western diet is detrimental to microbiome health and may contribute to digestive issues. Western diets are generally high in sugar, refined carbohydrates, animal proteins, and calories and low in fruits, vegetables, and dietary fiber. (6)(7)

Individuals with food allergies or intolerances may benefit from an elimination diet to identify dietary triggers and/or to help manage their symptoms. (3) One example is the low-FODMAP diet, which eliminates a group of poorly digested carbohydrates and polyols and is commonly used in the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders. (18)3. Be mindful of your meal sizes

If you suffer from digestive problems such as GERD or functional dyspepsia, having large meals may trigger your symptoms. Consuming smaller meals is often recommended as part of the treatment for these conditions. (9) Watch your portion sizes by using smaller plates and bowls, reviewing nutrition facts labels for appropriate serving sizes, eating more slowly to allow your brain to recognize when your stomach is full, and practicing mindful eating. (15)4. Stay hydrated

Research has associated reduced fluid intake with an increased risk of constipation. Trials in individuals with constipation have examined the effects of increasing water intake to at least 68 oz (2 L) per day, either on its own or in combination with fiber supplementation. In both cases, increasing water intake may improve stool regularity. (12) To help maintain bowel regularity, ensure you drink at least 68 oz (2 L) of water daily.

Practicing yoga may help alleviate common digestive issues.

5. Practice yoga for digestion

Research suggests that regular yoga practice may help alleviate digestive issues. A systematic review found that practicing yoga is associated with decreased IBS severity, bowel symptoms, and anxiety, as well as improved physical functioning and quality of life in individuals with IBS. The authors note that further high-quality studies are needed to inform specific recommendations for yoga for digestion. (17) Download a handout on yoga poses for digestion.6. Exercise for digestion

Regular physical activity may have a protective effect against digestive problems such as IBD due to the anti-inflammatory effects of exercise. Trials in individuals with IBD suggest that regular exercise is associated with a reduced risk of progressing from remission to active disease state. Further, moderate exercise such as walking, running, or yoga can improve quality of life in these individuals. It’s important to note that moderation is key, as high-intensity exercise may trigger inflammation followed by immune function suppression. (2)7. Moderate alcohol consumption

Excessive alcohol consumption has been shown to result in dysbiosis, intestinal inflammation, and damage to digestive organs and intestinal lining (i.e., increased intestinal permeability). Chronic alcohol intake is associated with an increased risk of digestive diseases such as alcoholic liver disease and gastrointestinal cancers. (4) Current recommendations for alcohol intake in adults are a daily limit of two standard drinks for men and one standard drink for women. A standard drink is defined as a 12 oz (355 mL) regular beer (5% alcohol), a 5 oz (148 mL) glass of wine (12% alcohol), or 1.5 oz (44 mL) of 80 proof distilled spirits (40% alcohol). (19)8. Quit smoking

Cigarette smoke may harm the digestive system by damaging gut mucosa, impairing mucosal immune function, and irritating the gastrointestinal tract. Smoking cigarettes has been associated with an increased risk of many digestive conditions, including IBD, peptic ulcer disease, and colon, esophageal, liver, pancreatic, and stomach cancers. Speak to your healthcare provider for support and resources to help you quit smoking. (1) Did you know? Over 60 carcinogenic and harmful chemicals have been identified in cigarette smoke. (1)9. Get enough restful sleep

Research has found strong associations between sleep disturbances and digestive diseases, which may result from the increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines (substances created by immune system cells that promote inflammation) seen following sleep dysfunction. There appears to be a bidirectional relationship in which poor sleep may exacerbate gastrointestinal symptoms, and digestive issues may interrupt the sleep-wake cycle and harm sleep. (10) Visit the Fullscript blog for information on improving your sleep health.Did you know? Approximately 50 to 70 million Americans suffer from sleep disorders. (10)

The bottom line

You can maintain the health of your digestive system by incorporating certain lifestyle behaviors, such as consuming foods that help digestion, exercising, practicing yoga for digestion, and minimizing your exposure to substances such as alcohol and cigarette smoke. (3)If you’re a patient, speak to your integrative healthcare practitioner about how to improve digestive health before making significant lifestyle or dietary changes.- Berkowitz, L., Schultz, B. M., Salazar, G. A., Pardo-Roa, C., Sebastián, V. P., Álvarez-Lobos, M. M., & Bueno, S. M. (2018). Impact of cigarette smoking on the gastrointestinal tract inflammation: Opposing effects in crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Frontiers in Immunology, 9, 74.

- Bilski, J., Mazur-Bialy, A., Brzozowski, B., Magierowski, M., Zahradnik-Bilska, J., Wójcik, D., Magierowska, K., Kwiecien, S., Mach, T., & Brzozowski, T. (2016). Can exercise affect the course of inflammatory bowel disease? Experimental and clinical evidence. Pharmacological Reports, 68(4), 827–836.

- Bischoff, S. C. (2011). “Gut health”: A new objective in medicine? BMC Medicine, 9(1).

- Bishehsari, F., Magno, E., Swanson, G., Desai, V., Voigt, R. M., Forsyth, C. B., & Keshavarzian, A. (2017). Alcohol and gut-derived inflammation. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 38(2), 163–171.

- Chaudhry, N. A., Jacobs, C., Green, P. H., & Rampertab, S. D. (2021). All things gluten. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, 50(1), 29–40.

- Chiba, M., Ishii, H., & Komatsu, M. (2019). Recommendation of plant-based diets for inflammatory bowel disease. Translational Pediatrics, 8(1), 23–27.

- Conlon, M., & Bird, A. (2014). The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrients, 7(1), 17–44.

- Davani-Davari, D., Negahdaripour, M., Karimzadeh, I., Seifan, M., Mohkam, M., Masoumi, S., Berenjian, A., & Ghasemi, Y. (2019). Prebiotics: Definition, types, sources, mechanisms, and clinical applications. Foods, 8(3), 92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6463098/

- Grassi, M., Petraccia, L., Mennuni, G., Fontana, M., Scarno, A., Sabetta, S., & Fraioli, A. (2011). Changes, functional disorders, and diseases in the gastrointestinal tract of elderly. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 26(4), 659–668.

- Khanijow, V., Prakash, P., Emsellem, H. A., Borum, M. L., & Doman, D. B. (2015). Sleep Dysfunction and Gastrointestinal Diseases. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 11(12), 817–825.

- Kumar Singh, A., Cabral, C., Kumar, R., Ganguly, R., Kumar Rana, H., Gupta, A., Rosaria Lauro, M., Carbone, C., Reis, F., & Pandey, A. K. (2019). Beneficial effects of dietary polyphenols on gut microbiota and strategies to improve delivery efficiency. Nutrients, 11(9), 2216.

- Liska, D., Mah, E., Brisbois, T., Barrios, P. L., Baker, L. B., & Spriet, L. L. (2019). Narrative review of hydration and selected health outcomes in the general population. Nutrients, 11(1), 70.

- Livovsky, D. M., Pribic, T., & Azpiroz, F. (2020). Food, eating, and the gastrointestinal tract. Nutrients, 12(4), 986.

- Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K., & Knight, R. (2012). Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature, 489(7415), 220–230.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2021). Food portions: Choosing just enough for you. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/just-enough-food-portions#home

- Rezac, S., Kok, C. R., Heermann, M., & Hutkins, R. (2018). Fermented foods as a dietary source of live organisms. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 1785.

- Schumann, D., Anheyer, D., Lauche, R., Dobos, G., Langhorst, J., & Cramer, H. (2016). Effect of yoga in the therapy of irritable bowel syndrome: A Systematic review. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 14(12), 1720–1731.

- Thomas, J. R., Nanda, R., & Shu, L. H. (2012). A FODMAP diet update: Craze or credible? https://med.virginia.edu/ginutrition/wp-content/uploads/sites/199/2014/06/Parrish_Dec_12.pdf

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf

- Williamson, G. (2017). The role of polyphenols in modern nutrition. Nutrition Bulletin, 42(3), 226–235.