Nurse practitioners (NPs) are playing an increasing role in meeting healthcare demand across the U.S. Of the more than 385,000 licensed NPs, only about 140,000 practice in states that grant full authority to deliver care independently. Full practice authority (FPA) allows NPs to assess, diagnose, and treat without physician oversight.

Evidence supports the safety and effectiveness of NP care under FPA, with comparable outcomes to physician-managed care. FPA is also linked to improved access and reduced wait times, especially in rural and underserved areas.

This article reviews the clinical value of FPA, its impact on healthcare costs, and the policy landscape shaping its future.

Whole person care is the future.

Fullscript puts it within reach.

healthcare is delivered.

Historical Evolution of Practice Authority

The NP role began in 1965, pioneered by Dr. Loretta Ford and Dr. Henry Silver to address pediatric care shortages. Their model combined advanced clinical training with a public health focus, setting the foundation for what would become the NP profession.

By the 1980s, several states recognized the value of autonomous NP care and began granting FPA. These early adopters allowed NPs to assess, diagnose, and prescribe independently, creating a framework for future state-level reforms.

Several milestones have shaped FPA’s expansion:

- In 2010, the Institute of Medicine’s landmark report recommended removing scope-of-practice barriers for advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), emphasizing their capacity to provide high-quality, patient-centered care.

- The 2018 SUPPORT Act empowered NPs to prescribe medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder, reinforcing their role in behavioral health.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, emergency waivers temporarily expanded NP authority nationwide, accelerating legislative interest in permanent changes post-pandemic.

Defining FPA

The concept of FPA varies by jurisdiction, and understanding its definitions is essential for interpreting NP scope and policy implications.

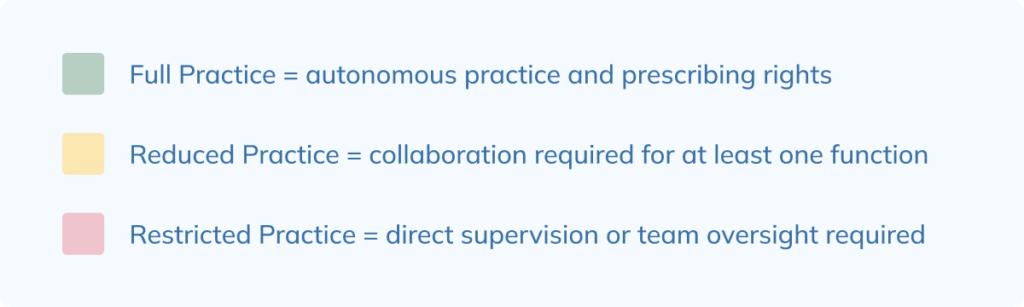

FPA grants NPs the ability to practice independently, including prescriptive authority, without mandated physician involvement. In contrast:

- Reduced Practice requires a collaborative agreement for at least one element of care.

- Restricted Practice mandates physician supervision or team-based oversight.

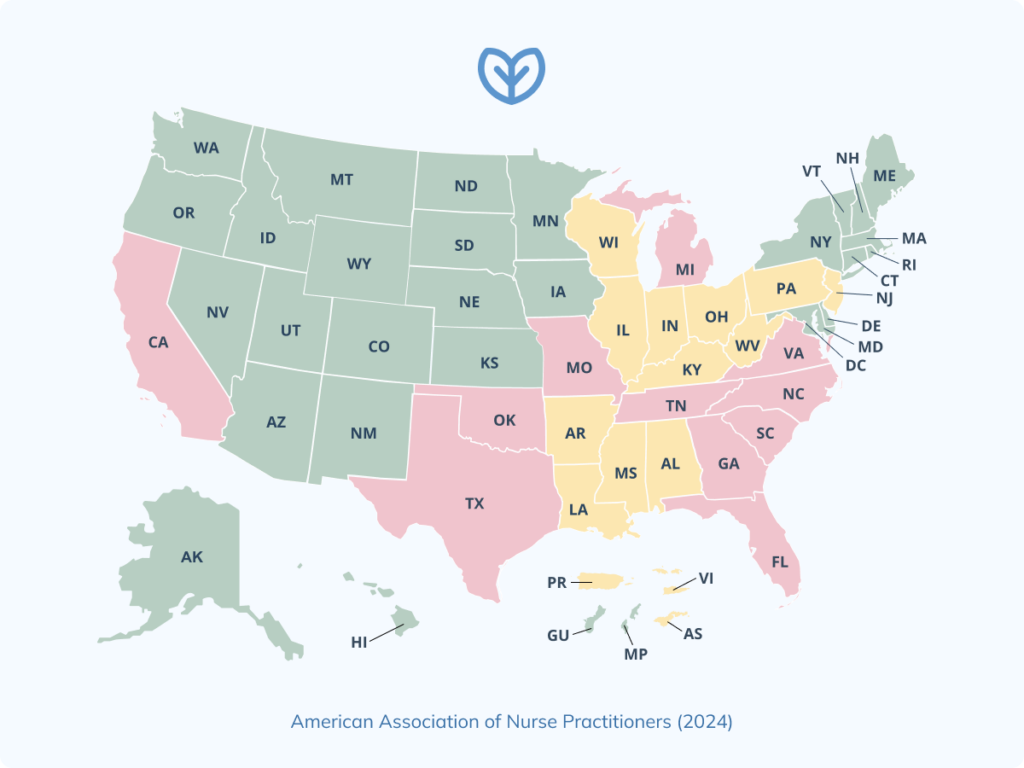

State boards of nursing regulate NP scope, creating a non-uniform national landscape. While some advocate for federal standardization, authority remains largely state-governed.

Practice authority can be summarized using this key:

As of 2025, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) map visually categorizes states by these levels.

Education and Certification Requirements

To qualify for independent practice, NPs must complete rigorous training and licensure steps:

- Graduation from an accredited graduate-level APRN program

- National certification through organizations like the AANP or ANCC

- Licensure and recognition by the state board of nursing

Ongoing requirements often include continuing education, clinical practice hours, and controlled substance registration. For example, in Illinois, NPs seeking FPA must complete a transition-to-practice period and obtain specific licensure for controlled substances.

Clinical Impacts of FPA

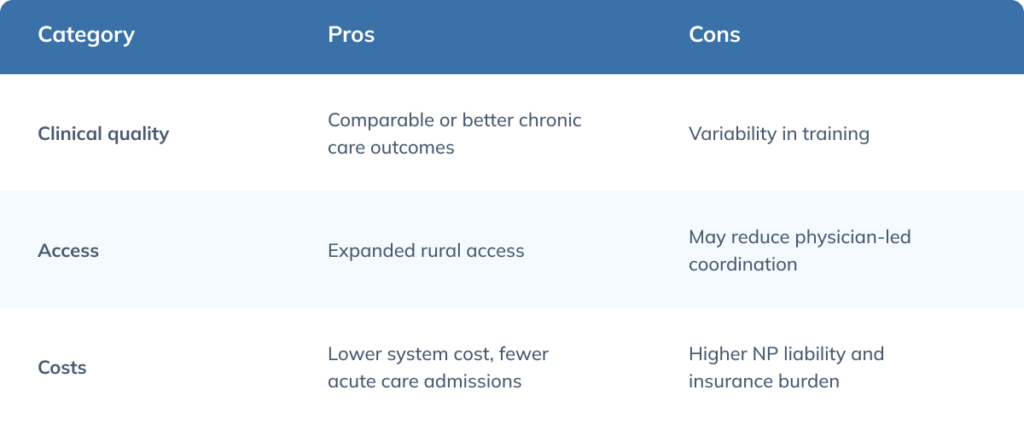

Granting NPs FPA has produced measurable benefits across care quality, access, and patient experience.

Patient Outcomes and Quality of Care

NPs practicing with FPA deliver outcomes comparable to physicians, particularly in chronic disease management. Evidence supports:

- Reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits

- Lower rates of readmissions

- Effective management of conditions like hypertension and diabetes

These improvements stem from timely care access and high adherence to evidence-based guidelines.

Access to Care and Rural Health Equity

FPA improves NP distribution in health professional shortage areas (HPSAs), especially in rural and underserved communities. In these areas, FPA is linked to shorter wait times for appointments and increased availability of primary care services.

By removing supervisory requirements, states with FPA enable faster deployment of providers where they are most needed.

Patient Satisfaction and Care Experience

Patients report high satisfaction with NP-led care, especially when NPs operate independently. Contributing factors include:

- Emphasis on patient education and shared decision-making

- Strong provider-patient relationships built on continuity and trust

- More time spent per visit compared to traditional physician encounters

These elements support improved engagement and adherence to care plans.

NPs and Public Health Challenges

NPs are key contributors to public health, particularly in areas with provider shortages. With FPA, their ability to address behavioral health and maternal care gaps increases.

Under the 2018 SUPPORT Act, NPs can prescribe medications for opioid use disorder, expanding access to substance use treatment. In solo rural practices, FPA enhances care continuity by allowing NPs to maintain uninterrupted services.

Economic and Workforce Outcomes

In addition to clinical benefits, FPA has significant implications for healthcare costs, workforce dynamics, and population health.

Cost of Care and System Efficiency

Healthcare delivery under FPA has been associated with cost savings, particularly in acute care and prescribing. By removing redundant supervisory steps, patient care is streamlined, reducing administrative delays and lowering system costs without compromising quality. This efficiency benefits both payers and patients.

NP Workforce Growth and Retention

States with FPA report stronger NP workforce growth, with more providers choosing independent practice. NPs in these settings experience better alignment between their training and job responsibilities, which can lower burnout risk. The ability to practice autonomously supports job satisfaction and professional longevity.

Comparative State-Level Health Indicators

States with FPA consistently score higher on national health benchmarks. For instance, Arizona, a long-standing FPA state, has shown reduced emergency room utilization and increased rates of preventive screenings. Overall, United Health Foundation data reflect better access and outcomes in states where NPs are allowed to practice independently.

Critiques and Concerns About FPA

While FPA for NPs has garnered broad support from many public health organizations, patients, and policymakers, it remains a point of contention among some stakeholders, particularly within segments of the medical community. These concerns span issues of training, quality assurance, system coordination, and professional dynamics.

Training and Clinical Preparedness

One of the most frequently cited critiques involves differences in clinical training hours between NPs and physicians. Opponents argue that the shorter duration and scope of NP education may limit preparedness to manage complex, multisystem diseases or make high-stakes diagnostic decisions independently.

Medical associations such as the American Medical Association (AMA) emphasize that physician education typically includes 12,000 to 16,000 hours of clinical training, compared to an average of 500 to 750 hours for NPs. From this perspective, the removal of mandated physician collaboration is seen as a risk to consistent, high-level care, especially in cases requiring extensive differential diagnosis or multidisciplinary oversight.

Continuity and Fragmentation of Care

Another concern involves care continuity. Critics caution that FPA could contribute to fragmentation if NP-led clinics or solo practices operate outside of traditional referral or hospital networks. In particular, systems without shared electronic health records (EHRs) or coordinated care protocols may experience lapses in information-sharing, redundant testing, or inconsistent chronic disease management.

While NPs practicing under FPA often emphasize collaboration and patient-centered continuity, critics argue that formal oversight requirements help ensure systemic integration and accountability, especially in settings with high care complexity.

Oversight, Accountability, and Quality Control

Some opponents contend that removing oversight could compromise quality control mechanisms. In traditional team-based models, physician supervision ensures that complex or borderline cases are escalated when needed. Critics argue that without formal checks, autonomous practice could lead to inconsistent standards of care, particularly across diverse practice environments.

Economic Competition and Workforce Dynamics

In some cases, critiques of FPA are rooted in broader workforce and economic dynamics rather than clinical concerns. Expanding NP autonomy may be perceived as encroaching on traditional physician roles, especially in primary care, where NPs are increasingly staffing roles once reserved for MDs.

This perceived “scope creep” has led to opposition from physician groups who view FPA as potentially destabilizing to healthcare hierarchies, reimbursement structures, and private practice viability. Critics worry that as more NPs operate independently, the financial incentives for physicians, particularly in underserved or rural areas, may diminish, potentially exacerbating existing physician shortages.

Liability and Risk Management

Liability is a common concern in debates about FPA for NPs. Some worry that independent practice could increase malpractice risk, particularly in complex cases without physician oversight.

However, data from insurers like the Nurses Service Organization (NSO) show NPs have low claim rates, and states with FPA haven’t seen consistent increases in malpractice premiums or lawsuits. While legal responsibility may shift more directly onto NPs in autonomous roles, especially in solo or rural settings, risk can be mitigated through strong documentation and adherence to clinical standards.

Current evidence doesn’t suggest that FPA leads to higher liability overall, though ongoing monitoring is recommended.

Interprofessional Collaboration and Oversight Gaps

One ongoing debate centers on whether formal collaborative agreements improve care compared to informal, team-based models. Critics argue that removing oversight could reduce interdisciplinary communication. Supporters note that organic collaboration can still occur without mandated supervision and may even improve under autonomous models.

Financial Burden on NPs Seeking FPA

Obtaining and maintaining FPA can carry financial and administrative burdens. These may include:

- Continuing education and transition-to-practice costs

- Increased malpractice premiums in some markets

- Start-up expenses for private or solo practice, including electronic health record (EHR) setup and billing infrastructure

These factors can create entry barriers, particularly for early-career or rural NPs.

Stakeholder Perspectives

Different stakeholders bring varying concerns and support to the FPA conversation:

- Physicians often highlight training differences and patient safety concerns

- Patients tend to prioritize continuity, access, and trust, which NPs often deliver effectively

- Healthcare systems value the flexibility and cost efficiency of NP staffing models

- Policymakers weigh FPA’s potential to reduce disparities and optimize workforce use

Pros and Cons of Full Practice Authority for NPs

Policy and Practice Landscape

The policy context surrounding FPA continues to evolve, influenced by legislation, healthcare system needs, and post-pandemic shifts.

State-by-State Overview of Practice Authority

As of 2025, 27 states and Washington, D.C., grant full practice authority to NPs. Recent developments include:

- Delaware adopting FPA in 2021

- California enacting phased FPA implementation starting in 2023

- Active legislation pending in states like Pennsylvania and South Carolina

This momentum reflects growing recognition of the NP role in addressing healthcare gaps.

COVID-19 as an Inflection Point

The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily lifted many supervisory restrictions through emergency waivers. These changes demonstrated that NPs could safely and effectively operate independently, prompting several states to make these adjustments permanent and accelerating legislative interest in FPA.

Institutional Policy and Payer Recognition

Despite legal authority, barriers persist at the institutional level. Challenges include:

- Lack of uniform credentialing and privileging processes

- Reimbursement disparities between NPs and physicians for equivalent services

These inconsistencies can limit the practical application of FPA in hospital and health system settings.

Post-Legislation Implementation Barriers

Even after legislative changes, NPs often encounter structural hurdles. These may involve:

- Restrictive hospital bylaws that lag behind state law

- Incompatibility with insurance systems, EHR platforms, or billing processes

Implementation support is needed for NPs to fully exercise their scope of practice.

Future Directions and Innovations

As healthcare evolves, FPA positions NPs to lead new models of care and leverage emerging tools.

Telehealth and Autonomous NP Practice

Telehealth has expanded opportunities for NP-led models, especially in behavioral health and chronic disease management. Hybrid and virtual-first clinics allow NPs to reach patients in remote or underserved areas, increasing continuity and convenience.

AI and Decision Support Tools for NP Independence

Artificial intelligence is being integrated into NP workflows to support clinical decision-making. These tools can:

- Enhance safety in solo or rural practice settings

- Standardize assessments and documentation

- Assist with complex differential diagnoses and care planning

Technology continues to lower the barriers to effective autonomous care.

Global Trends in NP Authority

Globally, countries like Canada, Australia, and the UK have adopted varying degrees of NP autonomy. International trends reflect a broader shift toward enabling NPs to practice to the top of their license. Comparative models offer insights into regulatory design, quality metrics, and workforce integration that can inform U.S. policy discussions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

The following answers address common areas of interest regarding legal scope, clinical impact, and operational realities for NPs working under FPA.

How does FPA affect NP prescribing privileges for controlled substances?

In FPA states, NPs generally have the authority to prescribe controlled substances without physician oversight, assuming they meet state-specific requirements. This often includes DEA registration, state licensure with prescribing authority, and completion of pharmacology coursework. Some states may require additional education or practice hours before granting full prescriptive authority.

What’s the evidence that FPA improves population health outcomes?

Research has shown that FPA is associated with improved access to care, especially in rural and underserved areas, which contributes to better preventive screening rates and reduced emergency room use. States with FPA tend to perform better in national health rankings related to access and chronic care management.

Are NPs in FPA states more likely to practice in underserved areas?

Yes, NPs are more likely to work in Health Professional Shortage Areas when they have full authority to practice. FPA enables flexible deployment of providers without delays linked to supervisory requirements, which improves geographic distribution and care continuity in resource-limited settings.

How do malpractice rates compare for NPs in FPA vs. supervised settings?

There’s no consistent evidence that FPA leads to higher malpractice risk. In fact, malpractice claim rates for NPs remain low across both FPA and non-FPA states. Insurers haven’t reported significant differences in liability exposure based on practice authority alone.

What are the credentialing and billing limitations for NPs with FPA?

Even in FPA states, NPs may face barriers in credentialing and reimbursement. Some institutions maintain privileging rules that restrict NP autonomy, and certain payers may reimburse NPs at lower rates or deny payment for specific services.

What happens if a hospital requires a physician’s cosignature even in an FPA state?

Hospitals can set internal policies that go beyond state regulations. If a facility mandates a physician cosignature or supervisory input, NPs must comply with those policies despite holding FPA. Changing these bylaws often requires internal advocacy and administrative support.

Can NPs in FPA states open their own clinics without restriction?

In most FPA states, NPs can establish independent clinics, though they must still meet standard business, licensing, and insurance requirements. Some states may have transition-to-practice requirements or collaborative agreements for new graduates before full independence is allowed.

How does FPA apply in multistate licensure compact scenarios?

The APRN Compact allows for multistate licensure, but it doesn’t override state-specific practice laws. An NP must follow the scope of practice laws in the state where the patient is located, even if they hold a multistate license. Therefore, FPA benefits only apply in states where such authority is recognized.

Key Takeaways

- Full practice authority enables NPs to assess, diagnose, and manage treatment independently, including prescribing medications where permitted by state law.

- Evidence supports FPA’s role in improving access, reducing costs, and maintaining care quality across diverse settings.

- FPA is associated with higher NP presence in underserved areas, improved patient satisfaction, and strong public health contributions.

- Implementation challenges persist at the institutional level, including credentialing, billing, and hospital policy alignment.

- Future innovations, including telehealth and decision-support technologies, will continue to expand the scope and efficiency of NP-led care.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as legal, regulatory, billing, or medical advice. While efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy and currency of the content, laws and practice authority regulations vary by jurisdiction and are subject to change. Readers should consult their state licensing boards, legal counsel, and relevant professional organizations for guidance specific to their practice and location.

Whole person care is the future.

Fullscript puts it within reach.

healthcare is delivered.

References

- AANP. (n.d.). Think Tank and Stakeholder Position Statements. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/advocacy-resource/think-tank-and-stakeholder-position-statements

- AANP. (2024, November 10). Governors Join With Patients To Honor Nurse Practitioners During National NP Week. American Association of Nurse Practitioners; AANP Website. https://www.aanp.org/news-feed/governors-join-with-patients-to-honor-nurse-practitioners-during-national-np-week

- Altman, S. H., Adrienne Stith Butler, & Shern, L. (2016, February 22). Removing Barriers to Practice and Care. Nih.gov; National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK350160/

- Amedari, M. I., & Ejidike, I. C. (2021). Improving access, quality and efficiency in health care delivery in Nigeria: a perspective. PAMJ – One Health, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj-oh.2021.5.3.28204

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. (2022). Standards of practice for nurse practitioners. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/advocacy-resource/position-statements/standards-of-practice-for-nurse-practitioners

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. (2024a). State practice environment. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/state-practice-environment

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. (2024b, August). Issues at a glance: Full practice authority. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/advocacy-resource/policy-briefs/issues-full-practice-brief

- Bae, K., Norris, C., Shakya, S., & Timmons, E. (2024). Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Full Practice Authority, Provider Supply, and Health Outcomes: A Border Analysis. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 25(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/15271544231212155

- Bischof, A., & Greenberg, S. (2021, May 31). Post COVID-19 Reimbursement Parity for Nurse Practitioners | OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. Ojin.nursingworld.org. https://ojin.nursingworld.org/table-of-contents/volume-26-2021/number-2-may-2021/post-covid-19-reimbursement-parity-for-nurse-practitioners/

- Boehning, A. P., & Haddad, L. M. (2023, July 17). Nursing practice act. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559012/

- Brom, H. M., Salsberry, P. J., & Graham, M. C. (2019). Leveraging health care reform to accelerate nurse practitioner full practice authority. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 30(3), 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1097/jxx.0000000000000023

- CDC. (2024, May 14). National Public Health Performance Standards. Public Health Professionals Gateway. https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/about/national-public-health-performance-standards.html

- Charalambous, J., Hollingdrake, O., & Currie, J. (2023). Nurse practitioner led telehealth services: A scoping review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 33(3), 839–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16898

- Davis, M., Dedon, L., Hoffman, S., Baker-White, A., Engleman, D., & Sunshine, G. (2023). Emergency powers and the pandemic: Reflecting on state legislative reforms and the future of public health response. Journal of Emergency Management, 21(7), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.0772

- DePriest, K., D’Aoust, R., Samuel, L., Commodore-Mensah, Y., Hanson, G., & Slade, E. P. (2020). Nurse practitioners’ workforce outcomes under implementation of full practice authority. Nursing Outlook, 68(4), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.05.008

- Doody, O., Graham, M., Hegarty, O., Slone, A. M., Walsh, P., Synnott, M., Russell, M., Dunworth, T., Sheridan, J., & Murphy, L. (2025). Identifying the landscape and contribution of advanced nurse practitioners in supporting healthcare provision in Ireland in the 21st century: An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 8, 100304–100304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2025.100304

- Dunbar-Jacob, J., & Rohay, J. M. (2025). State health and the level of practice authority for nurse practitioners. Nursing Outlook, 73(1), 102319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2024.102319

- Gardenier, D., Thomas, S. L., & O’Rourke, N. C. (2016). Will full practice authority mean higher malpractice premiums for nurse practitioners? The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 12(2), 78–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.11.013

- Harrison, J. M., Kranz, A. M., Chen, A. Y.-A., Liu, H. H., Martsolf, G. R., Cohen, C. C., & Dworsky, M. (2023). The impact of nurse practitioner-led primary care on quality and cost for medicaid-enrolled patients in states with pay parity. Inquiry, 60. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580231167013

- Henry, T. (2024, February 15). How scope creep is pushing beyond primary care. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/scope-practice/how-scope-creep-pushing-beyond-primary-care

- Htay, M., & Whitehead, D. (2021). The effectiveness of the role of advanced nurse practitioners compared to physician-led or usual care: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 3(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100034

- Illinois Nursing Workforce Center. (n.d.). 2022-06 Illinois APRN Continuing Education Re-licensure FAQs. Nursing.illinois.gov. https://nursing.illinois.gov/nursing-licensure/continuing-education/2022-06-illinois-aprn-continuing-education-re-licensure-faqs.html

- Khosravi, M., Zare, Z., Mojtabaeian, S. M., & Izadi, R. (2024). Artificial intelligence and decision-making in healthcare: A thematic analysis of a systematic review of Reviews. Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology, 11(23333928241234863). https://doi.org/10.1177/23333928241234863

- Kleinpell, R., Myers, C. R., & Schorn, M. N. (2023). Addressing barriers to APRN practice: Policy and regulatory implications during COVID-19. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 14(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2155-8256(23)00064-9

- Lohse, J., & Lerner, B. (2018, October 15). AHLA – SUPPORT Act: Highlights of the 2018 Opioid Legislation. Www.americanhealthlaw.org. https://www.americanhealthlaw.org/content-library/publications/bulletins/d73a0f8e-2dd3-4637-84f3-2b9029ee276f/SUPPORT-Act-Highlights-of-the-2018-Opioid-Legislat

- McMenamin, A., Turi, E., Schlak, A. E., & Poghosyan, L. (2023). A systematic review of outcomes related to nurse practitioner-delivered primary care for multiple chronic conditions. Medical Care Research and Review, 80(6). https://doi.org/10.1177/10775587231186720

- O’Connor, A., Helfrich, C. D., Nelson, K. M., Sears, J. M., Penny Kaye Jensen, Engstrom, C., & Wong, E. S. (2023). Full practice authority and burnout among primary care nurse practitioners. Nursing Outlook, 71(6), 102056–102056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2023.102056

- Peters, C. J. (2023). Dr. Loretta C. Ford: A pioneer in healthcare. Public Health Nursing, 40(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.13192

- Scott, B. A. B., & Manning, M. R. (2022). Designing the collaborative organization: A framework for how collaborative work, relationships, and behaviors generate collaborative capacity. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 60(1), 149–193. sagepub. https://doi.org/10.1177/00218863221106245

- Stucky, C. H., Brown, W. J., & Stucky, M. G. (2020). COVID 19: An unprecedented opportunity for nurse practitioners to reform healthcare and advocate for permanent full practice authority. Nursing Forum, 56(1), 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12515